About Bilbies

There is more to ‘why save bilbies’ than the fact that they look amazing, they have adorable ears and beautiful silky soft fur.

Firstly, bilby ancestors have been found as fossilised remains dating back 15 million years – which makes them a very special species. They have been an intrinsic part of the landscape across 70% of the Australian mainland for all that time. From the time Europeans arrived, bilbies stretched from the Great Dividing range in the east to the Gascoyne coast in the west.

Yet, in the last 100 years, they have been pushed to the brink of extinction as a direct result of colonisation, change in land use, population growth, and introduced non-native species.

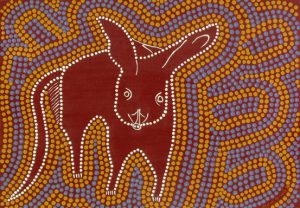

The bilby is also an animal at the heart of Australia’s First People’s culture and is a significant creature present in many dreamtime stories and cave art. CLICK HERE to see the most recently discovered and very ancient paintings, which include a bilby.

Secondly, bilbies are a scientific ‘flagship’ species. This means that their protection is even more important because their survival, in turn, increases the chances of 16 other threatened species and countless others who share the same habitats and threatening processes in the wild.

Bilbies are one of nature’s eco-engineers, they play a really important part in the restoration of soil and rejuvenation of vegetation in arid Australia. They use their strong front paws to dig deep burrows, which spiral down into the ground for roughly 2 metres.

They love to dig!

In doing so, they create many disturbances in the compacted and hardened soil, allowing plant material to fall in and decompose. At the same time, the soil is aerated, which supports seed germination.

Bilbies essentially create numerous compost pits every night.

That’s nature’s perfectly balanced ecosystem at work, which is at threat from the continued loss of bilbies. Where they have disappeared, hard-hoofed animals compact the surface of the ground and water, when it comes, reacts in a different way. Instead of soaking in, it runs straight off and, in doing so, changes flood patterns, which in turn changes the balanced ecosystem of arid Australia.

Bilby habitats also give protection to other endangered species – brush-tailed mulgara and spinifex hopping mice permanently occupy bilby burrows. A further two species – short-beaked echidnas and sand goannas – regularly use bilby burrows for shelter.

In total, an additional 16 mammal, bird, reptile, amphibian and invertebrate threatened species were detected interacting with bilby burrows. There was no difference in the number of species using disused or occupied bilby burrows, indicating that even disused bilby burrows are important structures for other species.

So, saving the bilby from extinction also means saving other native species; plus, it will help restore the critically important ecosystems at play in arid Australia.

The bilby is a nocturnal, omnivorous marsupial in the order Peramelemophia (bandicoots), It can also be referred to as a dalgyte, pinkie, or rabbit-eared bandicoot. Strictly speaking, though, they are not a bandicoot, they are a family of their own.

Bilbies are the last of our Arid Bandicoots in Australia – there were six, and the bilby is the only remaining one, We lost the Lesser bilby (Macrotis leucura) in the 1950s. So when we refer to bilbies, we are really talking about Macrotis lagotis – the Greater Bilby.

‘Macrotis’ means big-eared in Greek. Rude!

Our First Nation’s people across Australia have many names for the bilby, too, such as Mankurr (Martu & Manjilyjarra people) and Ninu (Pitjantjatjara people). However, the word ‘bilby’ comes from the aboriginal word ‘bilba’ used by the Yuwaalaraay people and means ‘long nosed rat’.

The Greater Bilby is absolutely unique in looks. They can, of course, easily be distinguished by their long ears and the white crest on their tail.

Let’s talk about those ears – they are big! They can be as much as 66% of the body length of the bilby, providing an easy point of differentiation between bilbies and other marsupials. These ears are super sensitive – useful for listening for predators as well as prey. When they dig, their ears are above ground, so they can listen for predators approaching. Their ears are hairless and covered by a network of blood vessels, which helps to cool them. When they are relaxed, they go floppy.

Bilby’s eyesight is poor, and they are also super sensitive to light. They tend to emerge from their burrows an hour after dusk and return an hour or so before dawn.

Our beautiful bilbies are about the same size as a rabbit when grown, although adult females are usually around half the size of adult males. They have soft, silky fur that is ash grey over the top of the body but is white underneath. The fur is much softer than you expect, softer than a rabbit.

The bilby has a very characteristic tail, which is their biggest downfall and their most cryptic secret. The tail starts dark-coloured and then ends in a white crest, which hides a pink spur. We have no idea what that spur is for! And the white end? Well, one theory is that since bilbies run in a zig-zag, their white tail crest would flick the opposite way, and the predator would head for the ‘lure’ rather than the bilby itself. Unfortunately, with the rise of the feral cat, it now acts like a flag to invasive predators at night. They might just as well be wearing a head torch, so easy are they for cats and foxes to see.

Bilbies have impressive teeth – 48, razor-sharp and larger than other bandicoots. Everyone at the Fund who has had to handle a bilby has experienced these teeth on occasion and would prefer not to again! Bilbies are omnivores, so they eat vegetation, as well as insects and spiders. Their favourite food is bush onion or yalka, which usually appears after a fire. Their favourite food in our breeding facility is mealworms, and they are an excellent source of protein. They have a long sticky tongue and a long snout with a pink nose and an excellent sense of smell.

Bilbies’ hind legs are similar in shape to a macropod (kangaroo/wallaby) but with syndactylous (fused) toes and an enlarged fourth digit, making for a very distinct footprint. Their forelegs are extremely strong – right from birth – as they have to use them to climb from the urogenital opening up to their mother’s rear-facing pouch. The pouch is ‘upside-down’ so that when the mother digs, she is not shovelling dirt into her pouch.

Well, that’s a good question. The overall bilby population in the wild has suffered a catastrophic decline, largely due to the introduction of invasive predators to Australia and changes in land management practices, including fire and intensive agriculture. Over 80% of our remaining wild bilby populations only occur on Indigenous Protected Areas “IPA’S”, others are only safe behind large “Predator Exclusion Fences” or in captivity for breeding to support a National Recovery Plan for the species. This means that it is a massive challenge for all our bilby lovers to see one for real.

Bilbies’ natural habitats are spinifex grasslands and mulga scrublands in the hot, dry, arid and semi-arid areas of Australia. They are now only found living wild in remote parts of western Queensland, the Northern Territory and Western Australia.

They live in spiralling burrows, which they dig up to 2m deep. This depth helps to keep them safe from predators and also provides a constant temperature range of 23/24°C, as bilbies can become heat stressed. A bilby may have as many as 12 burrows, but a female will choose one as the natal burrow when she is ready to give birth.

The bilby digs a lot. This digging breaks up the soil and helps with composting. Their multiple homes mean that other species can use them for shelter, too.

The bilby is omnivorous, and its diet includes bulbs, fruit, seeds, fungi, insects, worms, termites, small lizards and spiders. One of its favourite plant foods is the bush onion or yalka, which grows in desert sand plains after fires.

Bilbies have adapted to survive in the absence of permanent water because, like the koala, they get most of their moisture from their food. This has been essential to their survival over millions of years. However, the fact that feral foxes and cats can now find artificial sources of water or are adapting to the harsh conditions means that they can now survive in the arid areas where previously the bilbies were near untouchable.

Bilbies are usually solitary animals, and the female bilbies tend to associate with males just to mate. Once pregnant, they have one of the fastest pregnancies of any mammal – just 12 – 14 days.

When the baby Joey is born, it looks like a baked bean with legs. (see images 3 and 4). It stays in its mother’s pouch for between 75 and 80 days and is independent about two weeks later. Female bilbies have a backward-opening pouch with eight nipples. The pouch opens backward so as not to be filled with earth while digging.

At around six months, a female bilby is sexually mature and can breed and usually has one or two young at a time. Although it is rare, she can have triplets. In a good season in the wild, bilbies can have up to four litters.

They live for about 5 to 7 years in the wild and up to 11 years in captivity.

Well, we are a tiny team. Kevin Bradley (CEO) is the only full-time employee, and each year for the last 5 years, he has spent over 300 days in the field, on the tools, in the fenced sanctuary where we are releasing bilbies for free living.

This very short video will give you an idea about Kev’s daily life. It’s a must-see!

The rest of the team – Lesley works part-time looking after the breeding program and facility in Charleville; Sara does all of the fundraising and bilby admin; and Beck has just come on board to help Sara with admin and manage Supporter Care. We admit we are small but we feel mighty in the face of adversity with the support of so many wonderful bilby lovers!

The Bilby sanctuary is a 25km2 area inside Currawinya National Park. The fence was designed to protect bilbies from feral animals and predators (feral cats and foxes mainly) to enable them to live and breed in safety. It opened in 2003 and cost $500 000 to build the 25sq km electrified predator-exclusion fence.

Much of the money raised at this time came from selling thousands of panels of the fence.

The key features of the fence are:

- the 400mm wire netting ‘skirt’ at the base of the fence on each side blocks invaders from burrowing in and bilbies burrowing out under the fence

- 4,100 short ‘springy’ wires pull the netting across to create a ‘floppy top’ which stops foxes and cats climbing over it

- 5,000 volts of electricity pulse through six surrounding wires, preventing emus and kangaroos from crashing into and damaging the netting.

Unfortunately, flooding in the area a few years after the project had started re-build the bilby populations, meant that the lower part of the fence rusted and failed in certain areas and before we knew it, we were back at square 1.

The Queensland Government committed $700,000 to replacing the bottom panel of the fence with stainless steel wire to make it impervious to corrosion from flooding events. The government made good, and the new fence panels were in place by 2018.

Since then we have been doing what we know best – which is helping to deliver on the National Recovery Plan by breeding genetically appropriate bilbies and releasing them to the sanctuary at Currawinya National Park.

Currawinya National Park falls close to the centre of the bilby’s former range in eastern Australia. Weather conditions there provide a reliable and diverse food supply. The reintroduction of bilbies to this park forms part of a national strategy to recover endangered species to either their former status or, at a minimum, to secure the status of existing wild populations.

The co-founders, Pete & Frank, worked on the Park and received full support for everything they did to start saving the bilbies and create the Fund.

Bilbies belong to all Australians, so any preservation attempts should be made on crown land rather than a private sanctuary.

That being said, Currawinya National Park is open to visitors, but they cannot see or access the fenced sanctuary.

Now that the area inside the Bilby Fence is free from feral cats, we have released bilbies already. Initially, it was just six trailblazers who were very carefully monitored and tracked. They have since been joined by 14 bilby pioneers and six little rippers. We *think* that there are maybe over 100 bilbies in the community now. But they are quite hard to count!

Cassandra Arkinsall (bilby_tracker on Instagram) is a PhD student who is studying bilbies – she is crunching the numbers of our recent dragging and transacs (counting footprints), and we are excited to see what they say.

The Fund is aiming for an insurance population for Currawinya of 400 bilbies.

This is little Star being released in 2019.

In Charleville, we have had the great favour of being able to construct a facility on government-owned land where we can breed bilbies and condition them for release to the sanctuary.

Lesley works with the recovery team to manage the genetic diversity of the Currawinya bilbies and bilbies that are being sent to other sanctuaries across Australia.

Maintaining this genetic diversity is key to the survival of the bilbies in all their former ranges.

At the breeding facilities in Charleville, we have welcomed 80+ bouncing bilby babies.

At the end of 2020, after a difficult year, we ran an appeal to start upgrading the crèches and bilby care areas.

The appeal was a success, and our Charleville bilbies now live in wonderfully sized crèches. Decked out with protective roofing, protective fencing and netting. The bilbies have room to forage, burrow and breed up in perfect, safe conditions.

The Charleville breeding facility is key to saving bilbies not just for the sanctuary at Currawinya but across Australia. No other organisation has been as successful as the Fund at getting everything right to produce so many young.

We aim to build our community to reach around 400 free-living bilbies behind the fence, who, if the feral populations are controlled, might start to expand further into the park.

On another point, we suspect that there may be a wild bilby population in the Birdsville area. We would very much like to survey this area to establish whether there are bilbies and then consider how best to use our knowledge to protect that community, plus perhaps even borrow some genetics.

We still very much live ‘hand-to-mouth’ and have to fundraise frenziedly to finance each step of the way, we are very grateful that so far, we have kept on track, and so many Australians have helped us!

Fossil remains of bilby ancestors have been identified as 15m years old, so naturally, they feature in First Nation People’s Dreamtime.

In 2016 the Ninu Festival was held in Kiwirrkura, NT. The festival was for all people interested in the Bilby or Ninu. The Festival brought together Aboriginal rangers, traditional owners, Bilby custodians, scientists and others involved in landcare and land management.

Most of what we understand about the bilby’s role in First Nation People’s culture was reaffirmed at the festival and explored further – here are some interesting highlights.

Bilby Names

Across Australia, Aboriginal people speak or relate to the languages of their ancestors. Many people are proud of their languages and talk to keep them strong. Plants and animals have their own names in different languages. Species that are useful, important or valuable are named. There can be many meanings in a name.

One Aboriginal language may have several names for one animal. There may be several spellings of a name due to different alphabets used (orthographies). People are often fluent in several languages; they can switch between names.

Ted Fields and Nardi Simpson told us that the Australian common name bilby comes from the Ullaroi/Yuwaalaraay name Bilba or Bilba bilba in plural. For them, this relation to their ancestral language helps to keep the animal strong even though its physical form is no longer found on their country. It was interesting to learn that the Australian common name derives from an Aboriginal language. Another common name is Dalgite from the Nyungar/Nyoongar name – Dalgayt.

A paper,’ Aboriginal knowledge of the mammals of the Central Deserts’ (Burbidge et al. 1988:20), records many names for Bilby. It lists 29 Central Desert Aboriginal dialects or languages, about 97 names for Bilby; these include synonyms or similar names, so they may not all be different.

The bilby is a very important animal for First Nations People. At Kiwirrkura, it is called ‘Ninu’, hence the name of the festival. (By the way, unusually, many languages have a separate name for the Ninu’s tail – because it was super valuable.)

The Ninu Festival was held at Kiwirrkura because Aboriginal experts in Ninu ecology and tracking reside at Kiwirrkura. Ninu is one Pintupi name for Bilby. Populations of Ninu live close to the Kiwirrkura community. There are Ninu Tjukurrpa (dreaming) places nearby.

Like most Australian animals, the bilby was a meat animal because people needed food. The Ninu tail was made into body decorations that celebrated the beauty and virility of women and men. Bilbies were also a part of Tjukurrpa stories that connect people to places and people to each other along songlines.

Just as Ninu is a threatened animal, historical knowledge about Ninu is also threatened – old people who pass away take with them experiences, memories and practices that were vital to the care of desert lands. To learn, record and apply this knowledge is a serious task for rangers and others.

Aboriginal cultural sites associated with Ninu Bilby are scattered across Australia. One Ninu site called Tjiturrurr (or Tjiturrulungu) is about 100 km east of Kiwirrkura near the Western Australian – Northern Territory border. In opening the Ninu festival, custodians for Tjiturrulungu and the surrounding country met there with people who travelled from the east.

By visiting Tjiturru, we honour its custodians and their ancestors. There is a detailed story for Tjiturrurr, but it could not be shared publicly. The anthropologist David Brooks has a record that describes the site, its dreaming, its mythology, economic and historical significance, ownership and more (D. Brooks Notebook 5, pp 21,138-141).

First Nations People and the bilbies of one place are related by Tjukurrpa to those Ninu in another place and another place, and so on along lines that cross the country. So, custodians in one place can make connections to custodians in other places. They do this through their responsibilities to look after the sites, songs and stories for the animals. Sharing these animals and their stories helps to connect people over thousands of kilometres.

Here are some of the quotes from participants of the festival

“Ninu is important for Anangu, for us mob, for everybody.” (Sally Butler)

“The Australian government is committed to saving the bilby from extinction.” (Gregory Andrews, Australian Threatened Species Commissioner )

“We need to save the bilby to keep Australia alive. To keep our connections alive.” (Kirsty Hargraves, Wiradjuri Western Plains Zoo)

“It’s an iconic animal that a new generation wants to see.” (Leonie Anderson, Birriliburu)

“We need to save the bilby. They are extinct soon. All rangers need to work together and get the bilbies back in Australia.” (Aquinas Nardi, Ngangumarta)

“The bilby is the last arid zone Bandicoot left. It needs our attention.” (Stuart Dawson, Murdoch Uni)

“The Bilby is part of me. Part of this country. It makes my feeling so happy. The Bilby is on the country. I’m with him. My connection with the country. Me and the Bilby got one country to go walking.” (Rita Cutter, Birriliburu)

“We have to save the Bilby because we’ll be saving ourselves and our kids. The Bilby is us.” (Nardi Simpson, Yuwaalayaay, Bilba totem, Walgitt region, NSW and Taronga Zoo Education Officer)

“We’ve got to look after the Ninu. The Brushtail possum has gone. The Burrowing bettong is gone. The Bilby is the only one left. The Rufous hare wallaby has gone. The Pantawinta is gone. The possum is gone. The Northern quoll is gone. We’ve got to look after the Ninu.” (Noelia Ward, Kiwirrkura)

“Scientists recognise that the loss of Bilbies and the burrows it creates could contribute to the loss of other desert animals.” (Martin Dziminksi, WA Park)

At the festival, Gladys Nunarayi Brown read in Warlmanpa about Warrikirti (Bilby). Gladys offers us a special interpretation of the importance of Warrikirti. She alludes to a deep problem – if the animals are lost, then children cannot have a chance to see them, so how will they know them?

The need for children to see animals that are part of their country and family history is something that motivates many rangers and others who care for our country. Looking more at Gladys’ text below, she also talks about the ecology of Bilbies – what they eat, what eats them, their need for burnt patches, the effects of cattle, the keeping of Bilby at the Alice Springs Desert Park and more.

Kanumaju Warrikirti

Warrikirtima bandicoot-piya. Ngulyalu kalanya kantu kanjarrapurta, yalirlanyalu kanya kantu parra-kumari. Warrikirtima ngaka panya yakalurla, nyanganyalu yanunyjuku-kuma yakalurla.

Kanu yangkama-janalu ngarninya, pujikatirlu, winkiwarnurlu kapi wanganirlu.

Warrikirti, kartipanguma yirti-manya Bilbies. Ngarninyalu yama kapi witawita kuyu. Warrikirtingumalu kalanya lajuku kapi ngarninya jirlwi wanpaka-warnu. Winiwinima-jana partawurru ngulalu yalirlanya nyanganya yanunyju payingka- punganya. Warrikirtimalu maly-kangurra yangkangka ngurrangka muju, jalajalama wikartu wikartulkulu kanya.

Pujikartirli kapi winkiwarnurlu-janalu pakarnurra tartuma warrikirtima kapi-janalu yamangu kapi yangkangu wajirrkirlu, yangkaka yuluka manurra-janalu. Jalajalama kulajana winilku, kula-jana nganarlu winiwini-manya. Milanya yulungka ngulalu kanyanya puliki, pijarra warlmarimari kapi warrikirti ngulalu jinta-jangu, pulikingu- janalu muru-manurra nyaninya ngulya. Kayilpa-janalu partawurru-manmi, walkulu kanjinmi. Kayi walku, wal ngalu tatiyi palinyjinmi. Kulalu-janalu kurtukurtu-tarrarlu nyanyjinmilku kayilu palimima, warrikirtima. Yangkama warrakidima-janalu martanya kartipa-tarrangu. Martanya-janalu ngalu tartu-janyjinmi. Kayilu tartulku kami, ngarrajanalu pina yanyjinmi partawurru yuluka winiwinika ngalu partawurrurla kanyjinmi. Kartiparlumalu nyangu partawaurru yulumajana kakarni yantija N Karlantijpa ALT partawurruwma.

Poor thing Bilby

The Bilby (Warrikirti) is like a bandicoot. They dig a burrow deep downwards, where they avoid the sun (heat). Then the bilby goes out at night, looking for food during the night. Some of the poor things are eaten by cats, dingoes, and dogs.

Warrikirti, whitefellas call them Bilbies, they eat leaves and small animals. Bilbies dig for grubs and eat grass seed. Burnt grass patches are good for them, where they look for and find food. Bilbies used to be widespread in other areas, these days a few, there are a few now. Cats and dingoes have killed a lot of bilbies, and they have made the country different with other leaves and plants. These days, there’s no burnt grass for them now, nobody makes burnt patches for them. In this country where there’s bullocks, rabbits, and bilbies have come together, bullocks have blocked those burrows.

If we make them [?], there won’t be any. If [we do?] nothing, well, they’ll be all finished. The children won’t see them then when they will have finished, those bilbies. Whitefellas are keeping other bilbies. They are keeping them so they’ll become numerous, when there are a lot they’ll put them back in another area. When they put them back in good country, country with burnt patches, then they’ll improve. The whitefellas saw the country east [of Karlumpurlpa] across north Karlantijpa Aboriginal Land Trust is good for them.

(To give some background about this translated text – In 1998, this text was developed in English by Nic Gambold and Gladys Brown. Gladys, Nic and Fiona Walsh had seen Bilbies on Gladys’ family lands during land surveys. Gladys translated the text to Warlmanpa (see Gambold, Walsh and Brown 1998). Gladys later did Bilby surveys with Rachel Paltridge, then Jesse Carpenter and others. In preparing for the Bilby Festival, Gladys wanted to read this text in Warlmanpa. In May 2016, the text was translated back to English by David Nash and Gladys Brown.)

Nura Ward was a Ninu woman. She was a senior Pitjantjatjarra stateswoman, teacher and philosopher too.

Nura passed away in late 2013. The talk and photos of Nura were made available by Ara Iritija for the Bilby Festival. At the Festival, Fiona asked a Pitjantjatjara man who was family for Nura if it was OK for the audience to see these photos. He asked older women’s family members there. They said it was good to show Nura’s work and photos. They are very proud of her as a strong woman. She wanted a book to be made of her life and teachings; it was published in 2018 – Ninu Grandmothers’ Law.

These are Nura’s words:

Ngayulu Minyma Ninu. Ngayulu pakalpai Inma Minyma Ninu. Ngayuku ngunytjuku nguratja tjukurpa. Ilturta itingka, palu ini miilmiilpa, ngayulu putu wangkapai. Malu, Ninu, Mingkiri ankunytja, Coffin Hillta nguru Mintupaila kutu. Minyma Ninu ankunytja. Minymaku tjitji tjunkunytja. Watiku minymaku kutju kulintjaku. Paluru kanyiningi tjitji mankurpa: kutjara tjanangka munu kutju ampungka. Munu kutju tjuningka. Palumpa kuri anu Mintupaiku, inmaku, ka Minyma Ninu tjitji mankurpa tjara anu, kuri nyakunytjaku, Mintupaila. Palumpa kuri pitjangu, kuri pitjangu munu nyangu palumpa wife, munu paluru pukularingu.

Suzanne Bryce recorded and translated this as:

I am Minyma Ninu. I am Rabbit-Eared Bandicoot Woman. I dance Inma Minyma Ninu. This dance is my mother’s tjukurpa and comes from my mother’s country near Iltur (Coffin Hill). I cannot say the name of the place because it is too sacred to utter aloud. The place is connected to the journeys of Malu, Ninu and Mingkiri. They travel from near Iltur all the way over to Mintupai. Minyma Ninu herself makes this journey in order to give birth to her babies there. She walks there to be reunited with her husband. The details of this story are for senior men and women only. Minyma Ninu has two children with her: one she carries on her back and one she carries in her arms. One more is not yet born. This baby was born south of Walalkara. Her husband has gone to Mintupai for ceremonies, so Minyma Ninu travels there to be with him. When her husband comes out of the ceremonies to greet his wife, he is filled with joy and happiness.

Over thousands of years, Aboriginal people have said many things about Ninu. Whitefellas have recorded a few. These extracts show people’s observations of Bilby, what lies in old records and where to look to learn more.

In the 1980s, some scientists took the skins of rare or extinct animals on a tour to learn from desert people. Many Aboriginal people cried when they saw the old animals. For years, some remembered the ‘puppet show time’. The scientists wrote a paper,’ Aboriginal knowledge of the mammals of the Central Deserts’ (Burbidge et al. 1988:20), which includes information about the Bilby.

We used to follow the bilby’s path leading away. Maybe there would be a burrow there. We used to leave the two big ones in the burrow. We wouldn’t take the big ones home. We used to hit the little ones in the burrow. We hit them as we were digging along. He blocked his burrow. We used to dig along. “Wait on now, there’s a hole now, there’s one there now” We used to pull him out. We choked him. Only bilbies block off their burrows. The meat is medicinal; it’s very good to eat bilbies for colds. We used to cook them and cover them in the cooking trench (kilyirrpa). we cooked them just a little while, possums and bilbies… They cut off the white fluffy tail, only the white part on the tip of the tail. They bind it a little around a stick after threading it through before the ceremony. Yes. Bilbies are in my country. Around Yankirrikirlangu. North-east from Alekarenge. Many used to live there long ago. (Warlpiri Kuyu yumurru-kurlu, n.d.)

In the mid-1990s, the Threatened Species Network (TSN) also recorded Aboriginal people’s knowledge of Bilby and threatened species. Workers involved included Lizzie Giles (Ellis), Jenny Green, Myf Turpin, Robert Hoogenrad and Colleen O’Malley. From that project, there are pages of old people’s stories about different animals. These are held by the Central Land Council. One day, someone should write up and share these records.

The Bilby has always been like that. He was created with big ears; he listens with those two big ears. He listens for witchettys, for grubs that are nearby making noise… He pulls the witchetties out with his hands that he’s been digging with… He digs out the soft wood and, pulls them out from there and eats them. (Ruby Kngwarray, Eileen Ampetyan, Cookie Pwerl recorded in Kayteye, translated by Jenny Green and Myf Turpin at Stirling, 30.1.98, Tape no. 592 p1)

Bilbies used to eat grass, tarvine, aylperleny, bush onions … the root from the tarvine … The plant called aylperleny has disappeared. It’s like pencil yam, similar to tar vine, with yellow flowers. That animal has disappeared. (recorded in Kayteye and Anmatyerr, translated by J. Green M. Turpin at Stirling, 30.1.98, Tape no. 443 p5)

My granny used to dig and throw out the earth – that’s called ilkngwa. They dig down deep with a wooden dish [to hunt Bilby]… When I was a girl, I always used to sit on the heap of dirt at the side of the hole. On the ground, that the wooden dish had scooped out and thrown aside. I used to sit on the top. (ditto p3)

The whitetail was cut off, and the animal killed and eaten, and the tail cut off to make alpeyt. The apetyt was made into headdresses. Women’s ones. (Cookie Pwerl, Weetji Ampetyan, Ruby Kngwarray, Janie Ampetyan, recorded in Kayteye and Anmatyerr, translated by M. Turpin and J. Green Stirling, Tape no. 448 p1)

What happened? Maybe they went away. Maybe the bosses for Bilbies finished up, and they [the animals] finished up. The bosses for Possum finished up, too. The bosses died out, and the meat animals died out. (ditto p2)

Bilby’s tails are precious. Bilby’s tails relate to love and marriage.

Ninu have other uses and values beyond their meat or the Tjukurrpa stories they hold. Ninu have long tails. They carry their tails as they move. The end of their tail flicks up like the shape of a crescent moon. The tail is black along two thirds of its length with longer, looser white hairs at the end third. The white tail tips are very distinct and very valuable.

People used to separate and divide Ninu tail ends into tassels. One animal’s tail could make at least three tassels. The tail tassels were used in various ornamental ways and had deep symbolism. For some groups, the tails were associated with flirting, courtship, love, marriage, sexuality, procreation and related rituals. Some uses depend on the life stage of a person.

Ninu tail tassels could be attached to men’s hair belts or made into necklaces and other body decorations. Women twisted tail tassels were twisted into their hair to make themselves more beautiful and attractive. Men twisted Ninu’s tails into their beards to ‘make yourself flash’, meaning to attract the attention of women and others. Occasionally, tails were tucked in the rim of a cowboy hat (Doonday 2013). Women could be gifted a necklace of Ninu tails. Maybe tails had a symbolism like diamond rings.

In some places, Ninu tails were so valuable they were like money for some desert people. Daisy Bates, who lived at Ooldea, noted in 1929 that:

There is only one object that can be called money – the soft white tail tip of the rabbit bandicoot. Several of these attached to a man’s beard make him a rich man for the time being. Milbu is the central Australian term for this money, and every milbu has big purchasing power. Evidently, the rabbit bandicoot has never been numerous in central areas, and so its tail-tip becomes the only money of the interior. The milbu will buy many spears, a big bundle of hair of fur string, or even a wife. (T. Gara 1996 cited in Robinson 2003:221).

These decorations and their significance varied across Australia and for different people in different places. There are more accounts of exceptional values that countrymen and countrywomen gave to Bilbies that could be recorded. But some features of the Bilby are secret, so they cannot be written, heard or illustrated. There are other photos, poetry and songlines about Bilby, including some so strong that they would need special consultations with custodians before being published.

This animal was so important to desert men and women that it is likely that physical bilby populations were nurtured, cared for, revitalised and ‘managed’ in various practical ways to maintain or increase the animals.

Ninu helps to connect people. Across Aboriginal Australia, people connect through family, language, country and Dreamings. ‘Relatedness’ is a central and valued concept amongst Aboriginal groups. This relatedness includes people’s relationships with each other to animals and their songlines.

Some animals have skin names that directly connect them to people of related skins and moieties. Walmajarri people told us that for them, Ninu is of the Jampijimpa / Nampijimpa skin.

At the opening of the Ninu Festival, people said they wanted to make connections between each other – and they did. For example, people linked with each other through Tjukurrpa lines across different countries. People from Kiwirrkura and the Ngaanyatjarra lands networked and talked about Ninu and related animals.

There are Tjukurrpa sites, stories, ceremonies and songlines for the bilby. These occur in various places where Bilbies used to be found. Aboriginal people believe these places continue to hold the spirit, memory and power of the animals. The potential for bilbies to physically return to these places is always there.

People who hold Tjukurrpa for the animals would have been able to sing the sequence of places where the animals travelled. They may have done sand drawings of those songlines. On Ngaanyatjarra lands, there has been some regional scale mapping of Bilby songlines, but no other regional scale mapping is known today.

During the Ninu festival, many places were mentioned that hold Tjukurrpa for the animals. There is Tjiturrulungu, where we went on the first day. Other places mentioned were Kiwirrkura, near Yuendumu, near Tjirrkarli, near Warburton, near Jigalong, near Mulan, near Indulkana, near Pipylatjarra, near Wiluna, near Kalka, near Iltur (Coffin Hill), near Port Augusta, near Yarran Lakes and more. Other places that are noted in books, paintings and open sources that mention Aboriginal knowledge of Ninu include Pitjantjatjara lands (Mantapayika, Tjalku), Ngaanyatjarra lands near Tjirrkarli (Watja, Lake Breadon, Lurrpa-lurrpa, Wati Warta, Marrura) and on Yankunytjatjara lands.

At some sites, rounded and unusual stones were seen as the bodies of Ninu. Sadly, for custodians, some stones and sites have been removed or damaged, causing, by their interpretations, the animals to be less abundant.

Baker, Woenne-Green and Mutitjulu community (1993:104) wrote about the bilby:

“There is a strong Tjukurpa association between areas near Indulkana and around Mantapayika and Tjalku. It is here that Tjalku rubs its fingernails together in the Tjukurpa. Digging up opals here is digging up Tjalku eyes.”

Other people have spoken of similar associations. This indicates that there may be connections between Bilbies and objects that shine with colour or are iridescent.

Various Kimberley and northern desert people speak about an association between the Bilby and Guwan or pearl shells. Within Kimberley and desert cultures, carved pearl shells can become ceremonial objects (Akerman and Stanton 1994; Yu, Pigram and Shioji 2015). Ancient and desert-wide rituals involve the exchange of these pearl shells, knowledge and more by Kimberley and desert men.

Bilby as art

The bilby features in dreaming and in cave art. Many of our present-day bilby-loving community are also artists. Sometimes, we benefit from the sale of these beautiful bilbies, and sometimes, we just love to look.

Michael J Connolly

Munda-gutta Kulliwari

© Dreamtime Kullilla-Art